Mojo Is Not Ready for Advent of Code

Published:

It’s the end of the year, and that means that Advent of Code is over. I, like many others, find myself compelled to write about my experience solving this year’s puzzles.

This time last year, I considered—but ultimately rejected—using the novel Mojo programming language for Advent of Code. In 2023, Mojo simply wasn’t ready for the spotlight: it lacked too many essential features, and the pace of development was so rapid that the language grammar was shifting unpredictably from day to day. By December of this year, however, Mojo has stabilized (somewhat) and the standard library has been built out considerably.

Mojo seeks to be a replacement for Python. Its syntax is heavily influenced by Python; in fact, a lot of valid Python code is also valid Mojo code. But Mojo has advantages over Python: it’s compiled, statically typed, and has a borrow-checker. These characteristics mean it is potentially much faster than Python. (Mojo fans would want me to point out that Mojo has an additional set of advantages resulting from its ability to leverage hardware accelerators. These properties mean it is potentially even faster than C/C++/Rust under practical circumstances.) Since Mojo is so close to Python, it is almost as easy to write as Python. Consequently, Mojo advertises itself as a simple, ultra-fast language for Python users.

So for this year’s Advent of Code, I set out to answer the following question: Is Mojo good for Advent of Code?

The answer is no.

My experience with using Mojo to solve Advent of Code problems found it lacking in two fundamental ways.

- It’s not fast enough.

- It’s not easy enough to use.

Both points should be relatively shocking. Ease of use is a core development goal, and speed is the entire point. If Mojo can’t hit these targets, then it has no place in any code base.

1. Mojo isn’t fast enough

Arguably the more shocking revelation is that Mojo just isn’t that fast. In advertised use cases, Mojo can see a speed increase of up to 35,000x over Python. Of course, a lot of this speed increase comes from the use of hardware accelerators, vectorization, and parellelization. Nevertheless, the advertised improvement over pure Python without these enhancements appears to be 50-100x.

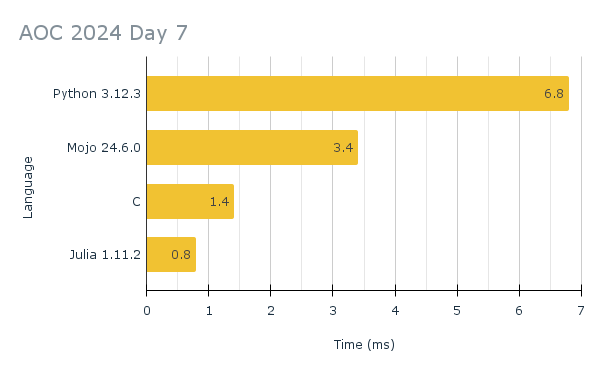

It turns out that although Mojo is highly optimized for floating point calculations, the rest of its computational abilities fall short. I benchmarked several languages on the AOC 2024 Day 7 challenge, and Mojo was a clear loser.

The challenge is to take a string of the form

190: 10 19

3267: 81 40 27

83: 17 5

156: 15 6

7290: 6 8 6 15

161011: 16 10 13

192: 17 8 14

21037: 9 7 18 13

292: 11 6 16 20

...

and determine, for each row, whether the number before the colon can be obtained from the remaining list of numbers. You are allowed the operations + and *, and must aggregate in sequence. So 190 is obtained via 10 * 19 and 292 is obtained via (11 + 6) * 16 + 20.

For part two of the challenge, you are also given concatenation as an operation.

I based my implementations on the exquisite Rust code written by github user maneatingape. My implementations (C, Julia, Mojo, Python) can be found here.

The solution is straightforward: iterate over the rows and extract the numbers. Then recursively attempt to generate the target number. It’s faster to do this backwards because you can trim entire branches of the search tree. For example, if the final element of the list of numbers is larger than the target, then it’s impossible to generate that target because all of the numbers are positive and so all of the operations increase the accumulating value.

Here’s the Python code:

def next_power_of_10(n):

if n < 10:

return 10

elif n < 100:

return 100

return 1000

def try_ops(line, target, idx, try_concat):

v = line[idx]

if idx == 0:

return target == v

if v > target:

return False

m = False

if target % v == 0:

m = try_ops(line, target // v, idx - 1, try_concat)

a = try_ops(line, target - v, idx - 1, try_concat)

if not try_concat:

return a or m

c = False

np = next_power_of_10(v)

n = target % np

if n == v:

c = try_ops(line, target // np, idx - 1, try_concat)

return a or m or c

def parse(inp):

p1, p2 = 0, 0

for line in inp.splitlines():

s = line.split(":")

target = int(s[0])

res = [int(v) for v in s[1].split()]

if try_ops(res, target, len(res) - 1, False):

p1 += target

p2 += target

elif try_ops(res, target, len(res) - 1, True):

p2 += target

return p1, p2

def main():

with open("input.txt", "r") as f:

inp = f.read()

p1, p2 = parse(inp)

print("Part 1:", p1)

print("Part 2:", p2)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

The Mojo implementation is basically the same, but with types and fn instead of def:

fn next_power_of_10(n: Int) -> Int:

if n < 10:

return 10

elif n < 100:

return 100

else:

return 1000

fn try_ops(line: List[Int], target: Int, idx: Int, try_concat: Bool) -> Bool:

v = line[idx]

if idx == 0:

return target == v

if v > target:

return False

m = False

if target % v == 0:

m = try_ops(line, target//v, idx-1, try_concat)

a = try_ops(line, target-v, idx-1, try_concat)

if not try_concat:

return a or m

c = False

np = next_power_of_10(v)

n = target % np

if n == v:

c = try_ops(line, target // np, idx-1, try_concat)

return a or m or c

fn parse(inp: String) raises -> Tuple[Int, Int]:

p1 = 0

p2 = 0

res = List[Int]()

for line in inp.splitlines():

s = line[].split(":")

target = atol(s[0])

for v in s[1].split():

res.append(atol(v[]))

if try_ops(res, target, len(res)-1, False):

p1 += target

p2 += target

elif try_ops(res, target, len(res)-1, True):

p2 += target

res.clear()

return p1, p2

fn main() raises:

with open("input.txt", "r") as f:

inp = f.read()

p1, p2 = parse(inp)

print("Part 1:", p1)

print("Part 2:", p2)

My C and Julia implementations use the same logic, though the C implementation has more customized parsing. I benchmarked each language’s performance and charted the results below. I timed only the execution of the parse function. That is, I measure how long it took the program to take the raw input (as a string) and compute the solution to both parts of the puzzle. I did not measure the time it took to read the file and store its contents in the string, and I did not include the print statements either.

Python is the slowest, unsurprisingly. Mojo is about twice as fast as Python. But the real story here is that Julia is about 4 times faster than Mojo!

(This is not meant to be a Julia propaganda post. Loyal readers will know I have plenty of complaints about Julia. Nevertheless, it’s amazing that Julia is better than a naive C implementation. To get C faster than Julia, I’d have to be smart and improve my custom parser.)

Standard library methods are slow

Much of Mojo’s performance issues can be traced to poor optimization for anything that isn’t a typical float computation. For example, I found that the String.startswith method is excruciatingly slow. I think this is because it punts the logic to StringSlice.startswith, which is implemented as follows:

fn startswith(

self, prefix: StringSlice[_], start: Int = 0, end: Int = -1

) -> Bool:

if end == -1:

return self.find(prefix, start) == start

return StringSlice[origin](

ptr=self.unsafe_ptr() + start, length=end - start

).startswith(prefix)

If the string doesn’t start with prefix, then the find call has to search the entire string for prefix. Stacking these inefficient methods on top of each other dramatically increases the overhead of simple operations.

Another example is String.splitlines(). The behavior of splitlines is identical to that of the corresponding Python function: it generates a list of strings between line breaks. Sadly, this means that iterating over rows is ineffecient; you have to allocate a potentially huge list in memory, even if you only use one line at a time (e.g., as you do in the Day 7 example).

An easier and faster way would be to have lazy iteration, like in Rust, where splitlines returns an iterator. The user can collect the iterator if they want, or they can call it lazily.

Lacking suitable profiling tools, Mojo remains very difficult to optimize. I had to discover issues like the startswith one by myself.

Something is wrong with stack allocation

A lot of potential optimizations come from stack allocating arrays, rather than constructing some dynamically sized monster on the heap. Any implementation of this in Mojo is necessarily un-Pythonic: Python stores nothing on the stack.

The current solution in Mojo is the InlineArray type. After some experimentation with this, however, I found that it does not yield any performance benefits, and inexplicably increases compile times by an order of magnitude.

2. Mojo isn’t easy enough to use

Mojo largely succeeds in being accessible to Python users (e.g., me) by keeping its syntax closely tied to that of Python. However, the more I used Mojo, the more times I found it to be stubborn, opaque, and confusing. I’ve collected my thoughts on the most prominent sharp edges below. Some of these overlap with those listed in the official Mojo roadmap, but many of them don’t seem to be considered issues, much less priorities.

Mojo is too verbose

Overall, I found myself annoyed with Mojo’s verbosity. Almost everything requires a huge number of qualifiers, keywords, and annotations. Other statically-typed languages look downright simple in comparison. When your language is uglier and slower than Rust, you have a problem.

The var keyword

Variable declaration has undergone an odd evolution in Mojo. Originally, variables were declared with one of two keywords: let and var. These were for declaring immutable and mutable variables, respectively, but designers ultimately chose to remove immutability (except in borrowed arguments—more on this later), so the let keyword was removed.

For a while, variables were declared with var, and then could be reassigned without a keyword:

var x = 10

x = 5

Recently, this pattern was deemed unpythonic, and so the var keyword was made optional. Now you can implicitly declare a variable by simply assigning it:

x = 10 # x is declared and set to 10

x = 5 # x is reassigned

But because of Mojo’s declaration rules, the var keyword has not been removed. You still need it, for example, in declaring structs:

struct MyStruct:

var x: Int

If you simply type x: Int, you get a compiler error. I don’t know why.

There are too many function argument keywords

Mojo employs a Rust-like borrow-checker, which means functions have three types of arguments:

ownedarguments, for which the function takes ownershipborrowedarguments, for which the function receives an immutable “reference” (semantically different from a reference, but that’s beyond the scope of the present discussion)mut(mutable) arguments, for which the function receives a mutable “reference”

The default argument type is borrowed, which can be specified with no keyword. This is great, because borrowed is an insane thing to type (c.f., Rust’s &). The keyword for mutable references is currently mut. This is a recent change: originally it was inout, signifying that the variable could both be read (“in”) and written (“out”).

But this is not the whole story. There’s a special argument type out, which is reserved for the __init__ method of a struct. For example,

struct MyStruct:

var x: Int

fn __init__(out self, x: Int):

self.x = x

The idea here is that when the struct’s constructor is called, the struct doesn’t exist yet, so it cannot be read. In other words, the inout concept for mutable arguments doesn’t make any sense here. You can only write to the structs fields. This is true, but weird, and the extra out keyword feels unnecessary. Since __init__ constructors are literally the only case where this special syntax is needed, why not have the out inferred? This creates an exception to the rule that default arguments are borrowed, but only in this one special case. Surely that’s better than an entire extra keyword.

But wait, there’s more! There’s a fifth function argument type: ref. These are arguments for “parametric mutability” (as the docs call it), i.e., for when you want to pass some mutable things and some immutable things. This ties in with Mojo’s increasingly convoluted Origin/Reference/Lifetime system (see previous link), and feels so categorically insane that I’m not going to bother trying to understand it. I can only assume this system will be removed soon.

Traits

Mojo uses a Rust-like trait system to specify interfaces and dynamically dispatch functions. The system is extremely powerful, allowing you to define function behavior for a large number of types simultaneously. There are a few built-in traits that the standard library uses extensively.

For example, CollectionElement is the trait used by List. You can make a List of anything that satisfies this trait, then define a function that works on any list with

fn my_func[T: CollectionElement](my_list: List[T]): ...

There’s a few points of friction with the trait system currently.

Combining traits is annoying

Suppose I want to define a function print_list that prints out all the elements in a list. Then I need the things in the list to (a) be CollectionElement and (b) be Writable. What I’d like to do is write something like

fn print_list[T: CollectionElement, Writable](my_list: List[T]): ...

The above doesn’t work. You can only specify a single trait for each parameter, so instead I have to create a new trait that combines both traits:

trait CollectionWritable(CollectionElement, Writable): pass

fn print_list[T: CollectionWritable](my_list: List[T]): ...

This tells the compiler that the new CollectionWritable inherits from both traits. I have to do this every time I want to use more than one trait, which turns out to be pretty often.

Tuple really needs to implement the KeyElement trait

It’s annoying to memoize a function in Mojo. In Python, the @cache decorator in functools allows you to easily memoize a function with hashable arguments. For example, in the Day 21 puzzle, my Python code contains this recursive function:

@cache

def do_dir_pad(path, depth):

res = 0

cur = A_KEY

for nxt in path:

paths = DIR_PAD_PATHS[(cur, nxt)]

if depth == 0:

res += min(len(p) for p in paths)

else:

res += min(do_dir_pad(p, depth - 1) for p in paths)

cur = nxt

return res

We could replicate this behavior manually by passing a cache dict instead. For example,

def do_dir_pad(path, depth, cache):

if (path, depth) in cache:

return cache[(path, depth)] # early return

res = 0

cur = A_KEY

for nxt in path:

paths = DIR_PAD_PATHS[(cur, nxt)]

if depth == 0:

res += min(len(p) for p in paths)

else:

res += min(do_dir_pad(p, depth - 1) for p in paths)

cur = nxt

cache[(path, depth)] = res # update the cache

return res

Since we can call do_dir_pad with an empty literal dict, the @cache decorator is only saving us 2 lines of code. To do this in Mojo, however, we can’t simply pass an empty (initialized) Dict[Tuple(String, Int), Int] (which is the type we need) because Tuple[S, T] doesn’t implement the KeyElement trait no matter what S and T are.

In order to make this work, we need to create a new type that satisfies this trait. It can look something like this:

@value

struct StrIntKey(KeyElement):

var s: String

var n: Int

fn __hash__(self) -> UInt:

return hash(self.s) ^ hash(self.n)

fn __eq__(self, other: Self) -> Bool:

return self.s == other.s and self.n == other.n

fn __ne__(self, other: Self) -> Bool:

return self.s != other.s or self.n != other.n

(Note how much mileage we’re getting out of the @value decorator! At least we don’t have to implement that ourselves.)

This is fine, but an annoying pattern. I already have in the same program a type that exists only to hash tuples of strings:

@value

struct StrKey(KeyElement):

var start: String

var end: String

fn __hash__(self) -> UInt:

return hash(self.start) ^ hash(self.end)

fn __eq__(self, other: Self) -> Bool:

return self.start == other.start and self.end == other.end

fn __ne__(self, other: Self) -> Bool:

return self.start != other.start or self.end != other.end

One solution to this is to use Mojo’s parametric typing system and create a kind of universal struct for hashing pairs of hashable things:

@value

struct HKey[T: KeyElement, U: KeyElement](KeyElement):

var t: T

var u: U

fn __hash__(self) -> UInt:

return hash(self.t) ^ hash(self.u)

fn __eq__(self, other: Self) -> Bool:

return self.t == other.t and self.u == other.u

fn __ne__(self, other: Self) -> Bool:

return self.t != other.t or self.u != other.u

For a moment, it feels like you’ve saved yourself a lot of work. However, this struct seems to break all type inference. For example:

t = String("foo")

u = String("bar")

x = HKey(t, u) # error

x = HKey[String, String](t, u) # works

You exchange verbosity in your type definitions for verbosity everywhere else.

This is all solved, of course, if Tuple ever implements the KeyElement trait. In principle, this should be very doable with Mojo’s new “conditional conformances”.

Traits can’t be implemented outside struct definition

This is a known “sharp edge”, but it completely undermines Mojo’s usability. Currently, you cannot define a trait implementation for a struct outside that struct’s definition. In Rust, you can implement anywhere. If a struct SomeonesStruct is defined in an external package, you can define a trait in your own package and implement it anyway:

trait MyCoolTrait {

fn do_thing(&self) -> isize;

}

impl MyCoolTrait for SomeonesStruct {

fn do_thing(&self) -> isize {

0

}

}

This means that no matter how annoying it is that a given type doesn’t implement a trait, there’s no way to fix it. The Tuple example is just one such. Another, more extreme version arose when I was trying to build out a library of convenience functions for Advent of Code.

I wanted to define a Grid type for storing 2d arrays. In practice, I intended Grid to mostly contain UInt8’s, but I needed it to be flexible enough to contain other things too. The definition looked something like this:

@value

struct Grid[T: CollectionElement]:

var height: Int

var width: Int

var data: List[T]

fn __getitem__(self, x: Int, y: Int) -> T:

return self.data[self.width * y + x]

I wanted to add a method find to Grid that returns the index of the first occurrence of some parameter in the Grid’s data. The implementation below does not work:

@value

struct Grid[T: CollectionElement]:

#...

fn find(self, needle: T) -> Optional[Tuple[Int, Int]]:

for i in range(len(self.data)):

if self.data[i] == needle:

return (i % self.width, i // self.width)

return None

Why doesn’t this work? It’s because we don’t know that objects of type T can be compared with ==. We can fix this by either updating the requirements on T in the definition of Grid, or we can use conditional conformance. To keep it simple, let’s add EqualityComparable to the requirements for T:

trait GridElement(EqualityComparable, CollectionElement): ...

@value

struct Grid[T: GridElement]:

#...

fn find(self, needle: T) -> Optional[Tuple[Int, Int]]:

for i in range(len(self.data)):

if self.data[i] == needle:

return (i % self.width, i // self.width)

return None

Great! This now compiles. The problem? It doesn’t work for the UInt8 type because UInt8 is not EqualityComparable. That’s right, Mojo does not know that it can detect whether two 8-bit integers are equal, and there’s no way to tell it how to do so.

“Value semantics” is weird and confusing

Mojo seeks to be more readble than its borrow-checked cousin Rust by having the default argument type be borrowed. It also employs what they’re calling “value semantics” so that the user never has to think about references.

This is, of course, impossible, because sometimes things are references. In the abstract, the value-semantics approach appears to be more Pythonic, but it pops up in unexpected places and causes some nontrivial—and decidedly un-Pythonic—problems.

For example, what is the behavior of this code? (Does it compile?)

fn my_func(a: List[Int]) -> Int:

b = a

b[0] = 50

return b[0]

fn main():

a = List[Int](1,2,3)

print(my_func(a), a[0])

It does compile, and it prints 50 1. This is because the statement b=a actually triggers a copy operation. That’s value semantics! But to the Python user, this code looks like it should cause an issue: a is passed as borrowed, which is to say, immutable, but the b=a statement in Python would simply bind b to the same list as a. Changing b is expected to change a, but it doesn’t. Here we see that value semantics can actually clash with the expectations of a Python user.

Using references would make this behavior much more explicit. In Rust, we’d have

fn my_func(a: &Vec<isize>) -> isize {

let mut b = a;

b[0] = 50; // error!

return b[0]

}

fn main() {

let mut a = vec![1,2,3];

println!("{} {}", my_func(&a), a[0]);

}

This causes a compiler error, because a is immutable and we can’t then borrow it mutably. Alternatively, using let b = a; causes a compiler error too, because b is now immutable. This is by design, of course.

Another annoying situation in which you actually want references is when building a collection (List, say) of objects that you don’t want to copy. You can customize copy/move behavior with the __copyinit__ and __moveinit__ methods, but you don’t always have power over these (if the struct is defined externally), and you don’t always want the same behavior.

In Rust, I can build a vector of references to anything. Ultimately, this means I’m passing around some pointer to a bunch of pointers, which can save me unnecessary allocations and copy operations. I can’t do this in Mojo, because of value semantics. I can only have List[T] where T implements CollectionElement. In principle I could make a list of pointers, but none of the pointer types implement CollectionElement!

Dynamic dispatch is broken without references

A common pattern in Rust is to take a bunch of things that each satisfy the same trait and create a vector of references (or pointers) to them.

trait MyTrait {

fn do_thing(&self);

}

struct MyStruct {

stuff: Vec<Box<dyn MyTrait>>,

}

There’s no error here. I can always create a vector of (heap pointers to) objects that satisfy MyTrait. The compiler can statically check that all I ever do with elements of stuff is call the trait methods (in this case, do_thing).

This allows Rust to dynamically dispatch the do_thing method at runtime, and gives a gentle form of polymorphism to Rust traits.

You can, of course, do a similar thing in Python (or any OOP language for that matter) using abstract classes and inheritance. Julia takes this to an extreme and allows you to dispatch on whatever you want, whenever you want.

This kind of dynamism is, for the moment, entirely absent from Mojo because there is no way to create a List of references or pointers to objects of the same type, much less to different types that all satisfy a given trait.