Ard Ri in Rust, Part 3: Alpha-beta Pruning

Published:

Last time, we implemented a basic minimax algorithm for searching the game tree. Today, we will improve that using alpha-beta pruning. The benefits of alpha-beta pruning are substantial. In the best-case scenario, the number of nodes it searches is roughly the square root of the number of nodes minimax searches. We will see such gains in practice.

Alpha-beta pruning theory

The idea of alpha-beta pruning is to add two parameters to our minimax search, alpha and beta. This will track, roughly speaking, the lowest score the maximizing player can guarantee and the highest score the minimizing player can guarantee, respectively. If the maximizing player is considering a node with a child whose value exceeds beta, then they can ignore that node’s siblings because the minimizing player would never allow the game to reach this node rather than the node whose value is beta. Similarly, if the minimizing player is evaluating a node with a child whose value is less than alpha, they can ignore the remaining children.

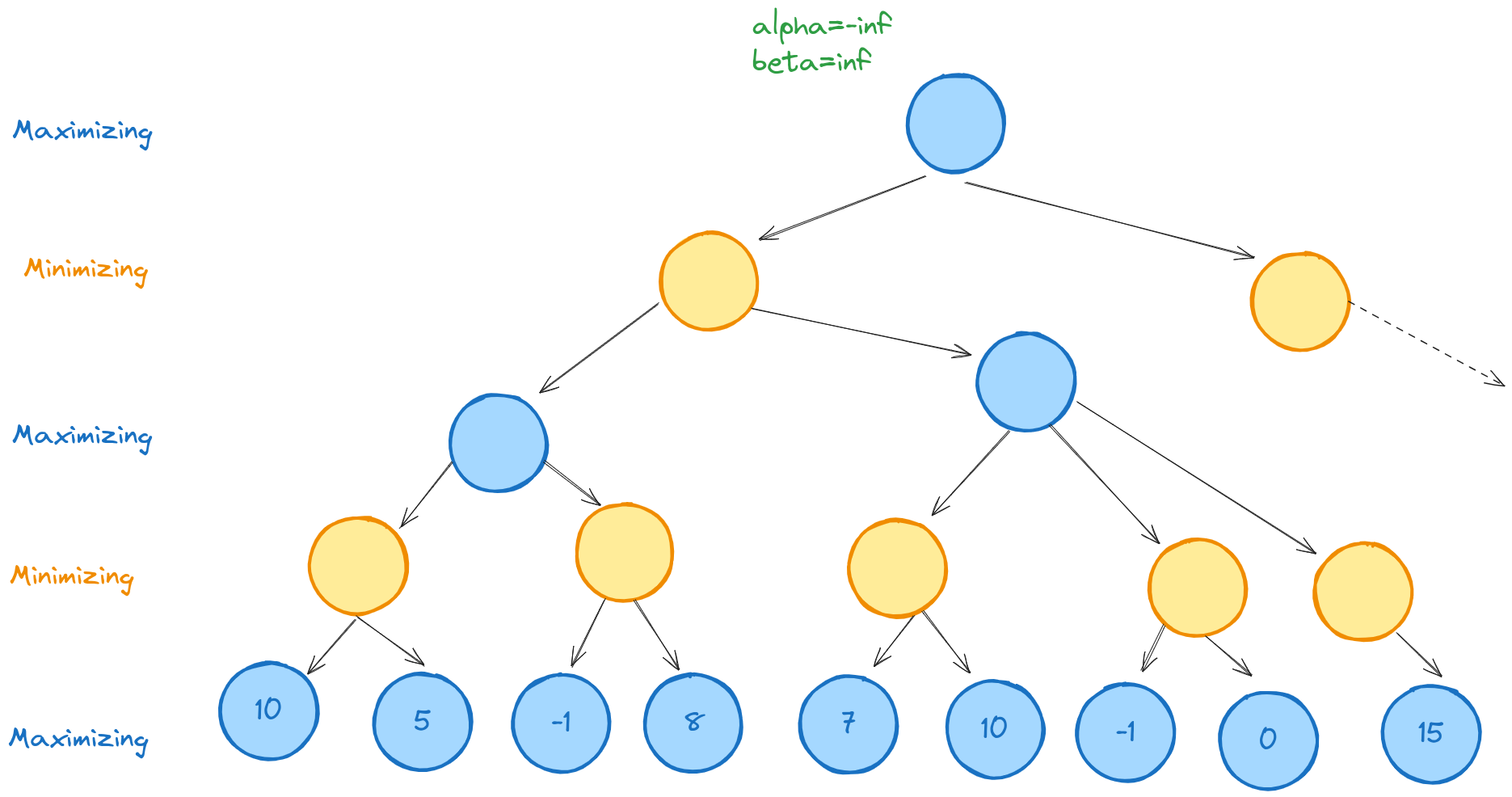

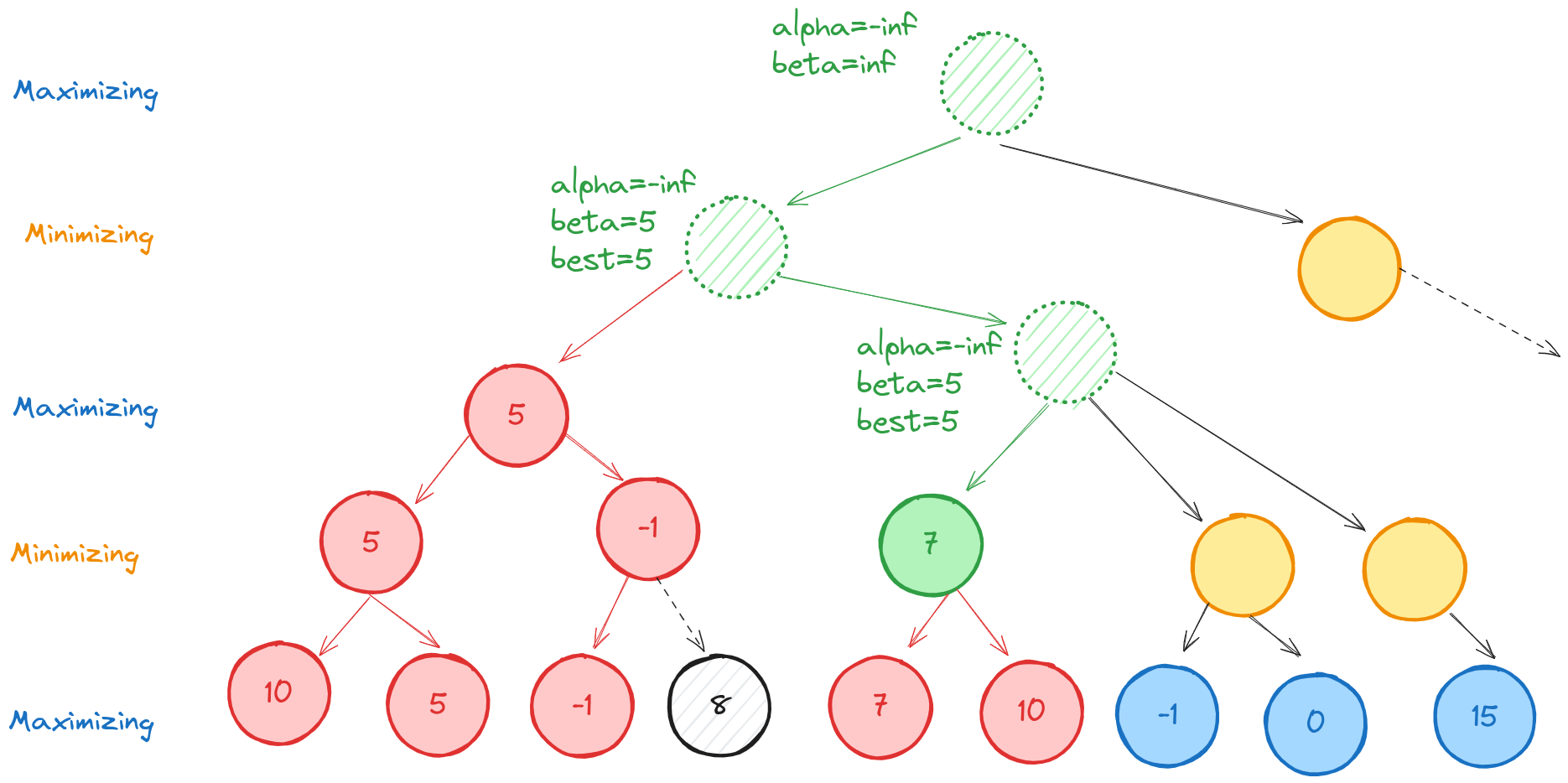

For example, suppose the maximizing player is evaluating a node like the one below.

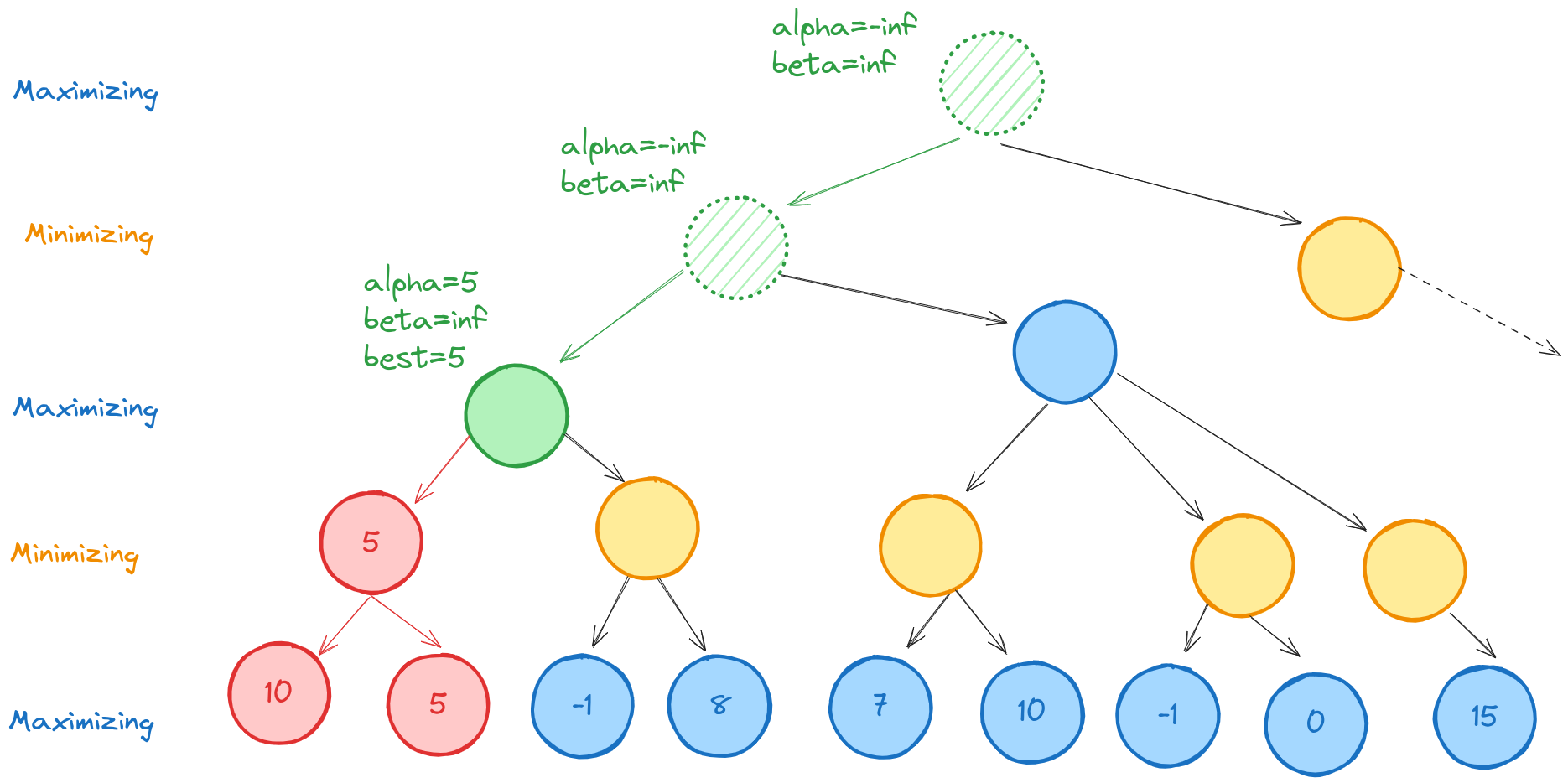

Alpha-beta-max first descends the left branches, evaluates the two terminal nodes, then their minimizing parent.

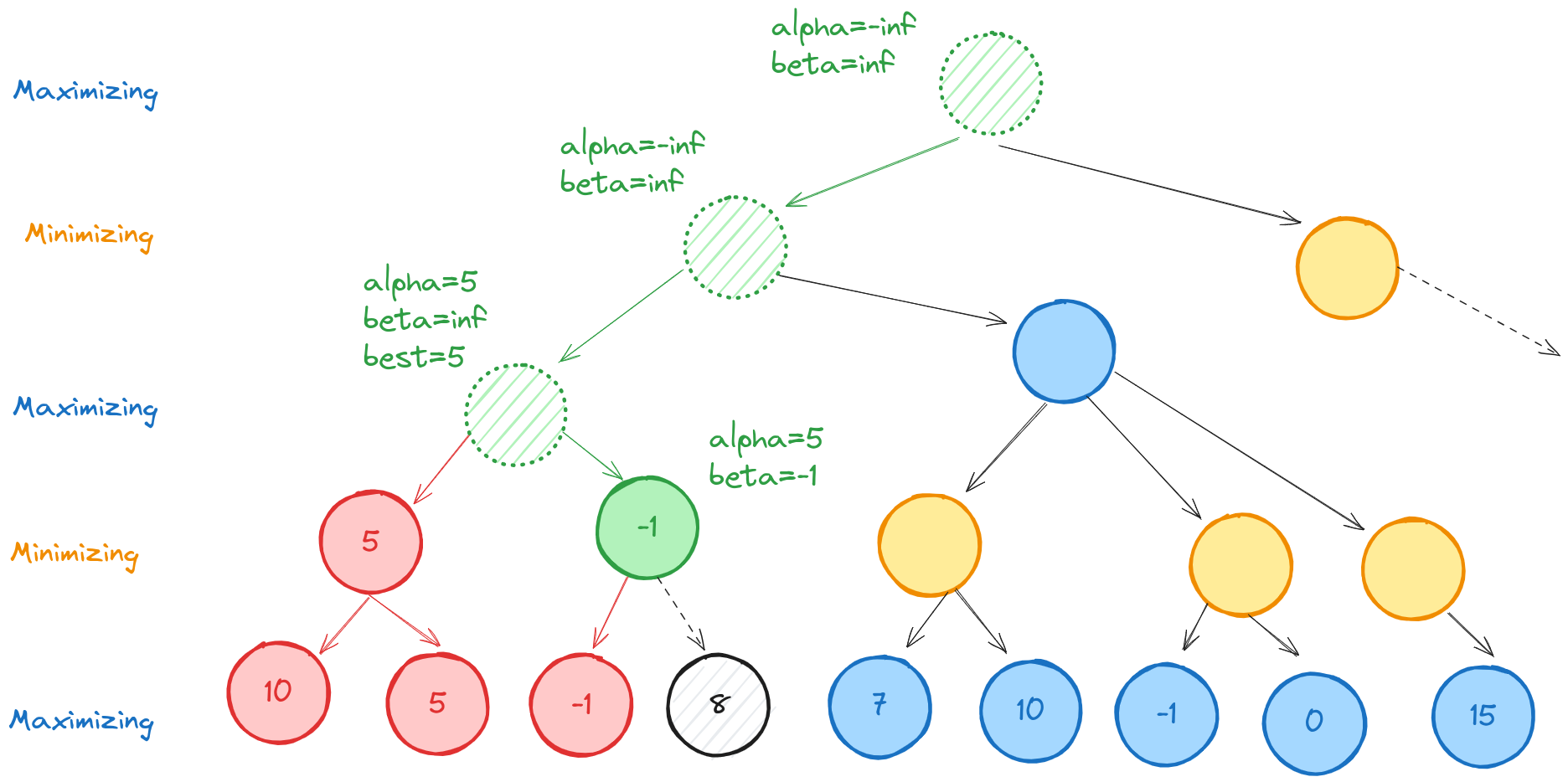

At this point, alpha=5, which is the best the maximizing player can currently do at the highlighted (green node). Descending to the next node, we evaluate its first (terminal) child, which has value -1. Since this is less than alpha, we know that the maximizing player will never allow the game to reach this node, so we can ignore its other child.

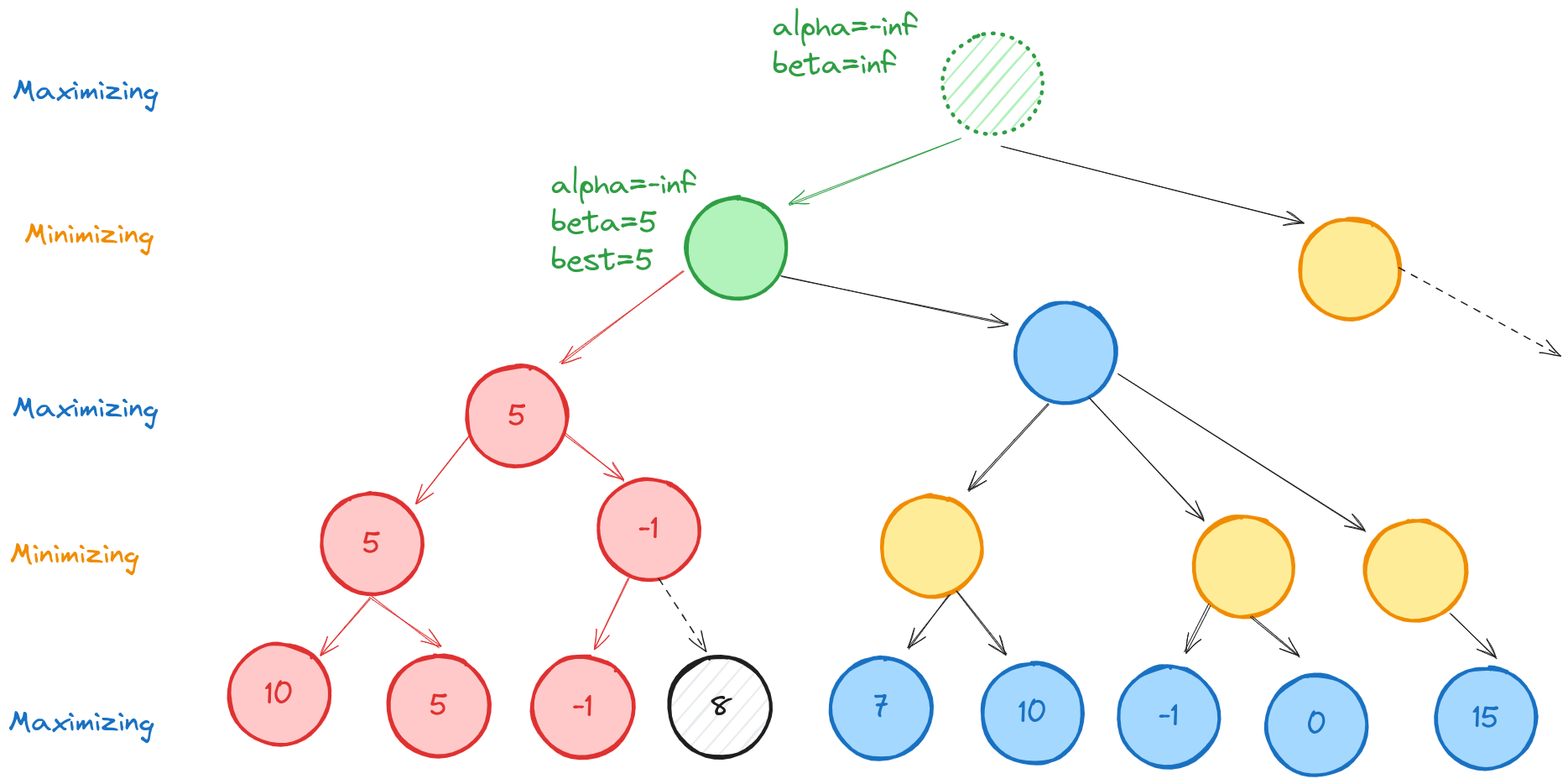

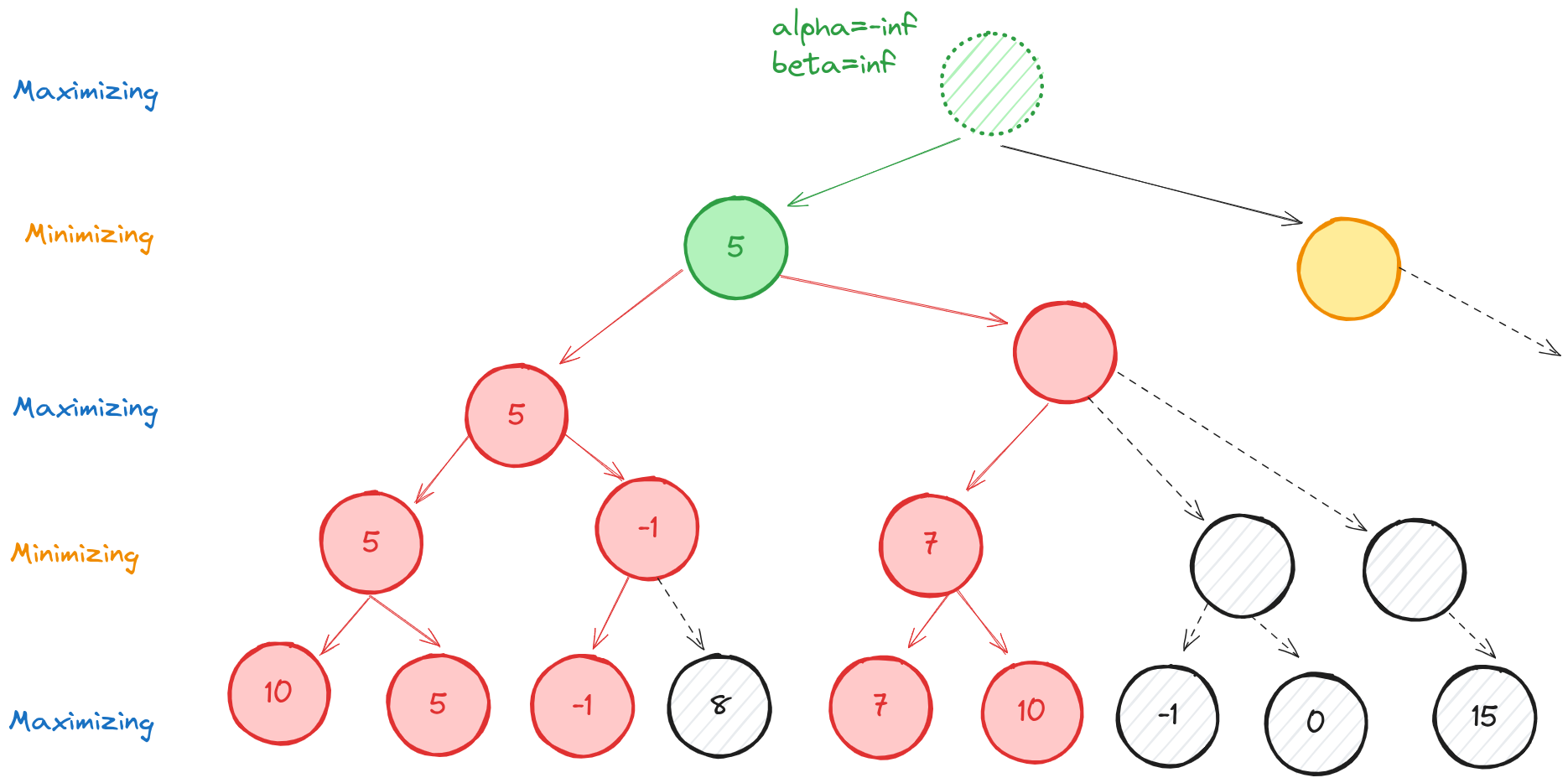

We now backtrack all the way to the highlighted green node, and mark beta=5, which is the best the minimizing player can do so far.

Descending to the right, then left, we evaluate the terminal nodes with values 7 and 10. Thus our green-highlighted node has value 7. Since beta=5 at its parent, the value of this node exceeds beta, and we can ignore its minimizing siblings. The minimizing player would never allow this node, so we don’t need to evaluate how much worse it could be for the minimizing player.

This means the left branch, depth one from the root has value 5. We never fully evaluated some of the tree, so we don’t know how good or bad those branches are for the maximizing player. All we know is that rational players would not allow those game states.

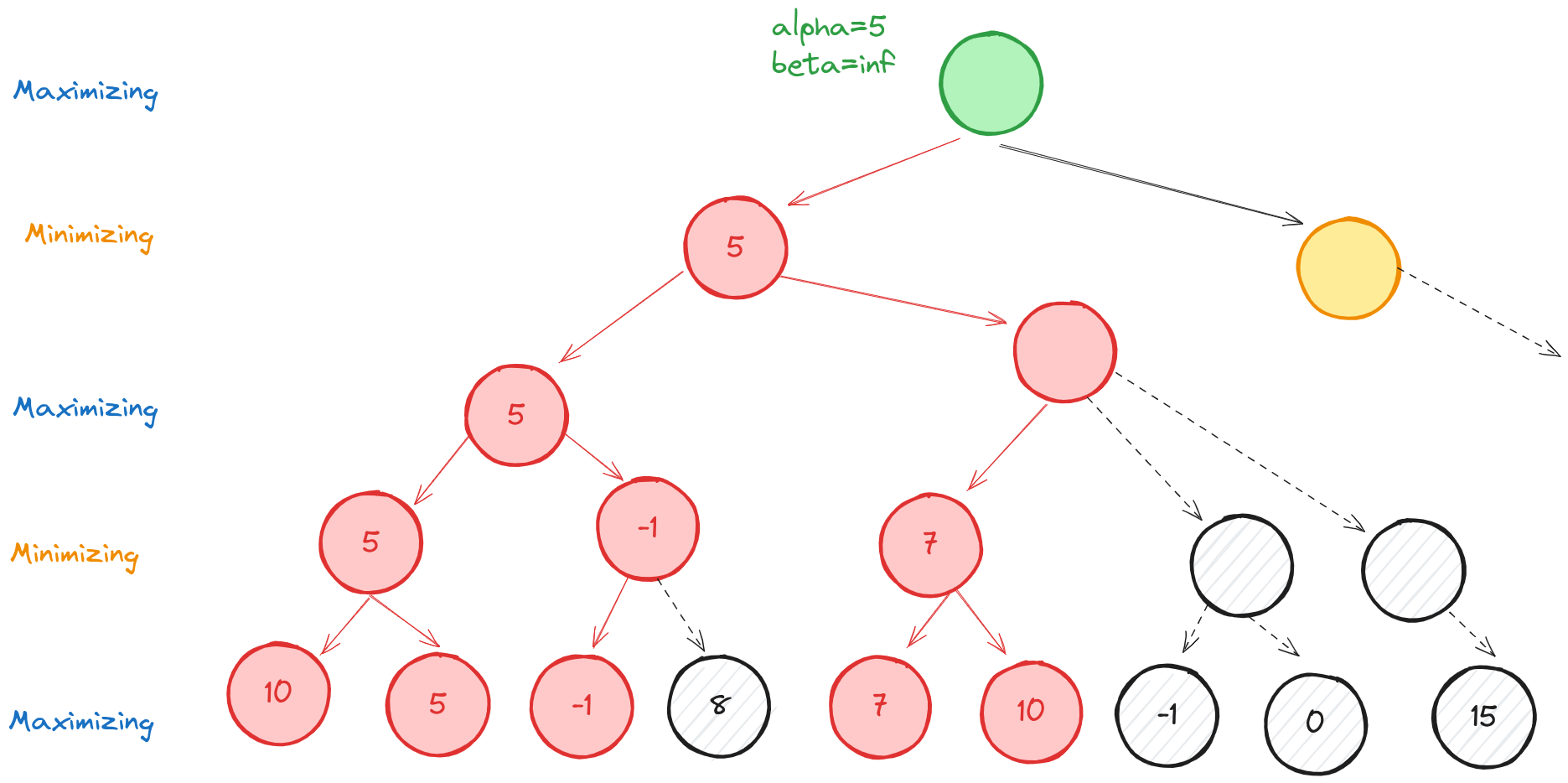

Finally, we update our root node and then we can explore the right minimizing child.

Alpha-beta pruning practice

In order to implement alpha-beta pruning, we need to update our engine.rs file. At risk of some code duplication, we’ll create two functions, alphabeta_max and alphabeta_min. These are the functions used by the maximizing and minimizing players, respectively. They recursively call each other as the active player swaps. The functions will start a lot like minimax. First, let’s look at alphabeta_max.

// engine.rs

fn alphabeta_max(

b: &Board,

depth: u8,

nnodes: &mut usize,

mut alpha: i16,

beta: i16,

) -> EngineRecommendation {

*nnodes += 1;

if depth == 0 {

return EngineRecommendation {

evaluation: naive_eval(&b),

best_move: NULL_MOVE,

nnodes: *nnodes,

};

}

if b.defender_win {

return EngineRecommendation {

evaluation: -10000 - depth as i16,

best_move: NULL_MOVE,

nnodes: *nnodes,

};

}

//...

}

Now we start searching for the best move, with an additional change: if we encounter a move whose evaluation exceeds beta, we return early and don’t search any more children.

// engine.rs

fn alphabeta_max(

b: &Board,

depth: u8,

nnodes: &mut usize,

mut alpha: i16,

beta: i16,

) -> EngineRecommendation {

//...

let mut max_eval = i16::MIN;

let mut best_move = NULL_MOVE;

// iterate through the children

for m in MoveGenerator::new(b) {

let new_board = b.make_move(m);

let rec_val = alphabeta_min(&new_board, depth - 1, nnodes, alpha, beta);

// update the best evaluation

if rec_val.evaluation > max_eval {

max_eval = rec_val.evaluation;

if max_eval == 10000 {

max_eval += depth as i16;

}

best_move = m;

// update alpha

if rec_val.evaluation > alpha {

alpha = max_eval;

}

}

// early return

if rec_val.evaluation >= beta {

return EngineRecommendation {

evaluation: rec_val.evaluation,

best_move: m,

nnodes: *nnodes,

};

}

}

return EngineRecommendation {

evaluation: max_eval,

best_move: best_move,

nnodes: *nnodes,

};

}

The code for alphabeta_min is basically the same.

// engine.rs

fn alphabeta_min(

b: &Board,

depth: u8,

nnodes: &mut usize,

alpha: i16,

mut beta: i16,

) -> EngineRecommendation {

*nnodes += 1;

if depth == 0 {

return EngineRecommendation {

evaluation: naive_eval(&b),

best_move: NULL_MOVE,

nnodes: *nnodes,

};

}

if b.attacker_win {

return EngineRecommendation {

evaluation: 10000 + depth as i16,

best_move: NULL_MOVE,

nnodes: *nnodes,

};

}

let mut min_eval = i16::MAX;

let mut best_move = NULL_MOVE;

for m in MoveGenerator::new(b) {

let new_board = b.make_move(m);

let rec_val = alphabeta_max(&new_board, depth - 1, nnodes, alpha, beta);

if rec_val.evaluation < min_eval {

min_eval = rec_val.evaluation;

if min_eval == -10000 {

min_eval -= depth as i16;

}

best_move = m;

if rec_val.evaluation < beta {

beta = min_eval;

}

}

if rec_val.evaluation <= alpha {

return EngineRecommendation {

evaluation: rec_val.evaluation,

best_move: m,

nnodes: *nnodes,

};

}

}

return EngineRecommendation {

evaluation: min_eval,

best_move: best_move,

nnodes: *nnodes,

};

}

Finally, we update the find_best_move method of TaflAI.

// board.rs

impl TaflAI {

pub fn find_best_move(&mut self, b: &Board) -> EngineRecommendation {

let mut nnodes = 0usize;

if b.attacker_move {

return alphabeta_max(b, self.max_depth, &mut nnodes, i16::MIN, i16::MAX);

} else {

return alphabeta_min(b, self.max_depth, &mut nnodes, i16::MIN, i16::MAX);

}

}

}

Wrap-up

I’m now able to crank the max_depth parameter up to 7 on the engine and evaluate positions in a second or less. At depth 8, it requires about 10 seconds for the more complex positions. This indicates a substantial improvement over the capability of our minimax implementation, which capped out around 5-6 depth for practical purposes.

At depth 8, playing a few moves looks like this:

7 # . V V V . #

6 . . . V . . .

5 V . O O O . V

4 V V O K O V V

3 V . O O O . V

2 . . . V . . .

1 # . V V V . #

a b c d e f g

Recommended Move: c3c2

Evaluation: 13 (2813265 nodes) (2.37s)

Make a move: c3c2

7 # . V V V . #

6 . . . V . . .

5 V . O O O . V

4 V V O K O V V

3 V . . O O . V

2 . . O V . . .

1 # . V V V . #

a b c d e f g

Recommended Move: e1e2

Evaluation: 13 (1286582 nodes) (936.02ms)

Make a move: e1e2

7 # . V V V . #

6 . . . V . . .

5 V . O O O . V

4 V V O K O V V

3 V . . O O . V

2 . . O V V . .

1 # . V V . . #

a b c d e f g

Recommended Move: c2c3

Evaluation: 13 (1263869 nodes) (1.03s)

Make a move: c2c3

7 # . V V V . #

6 . . . V . . .

5 V . O O O . V

4 V V O K O V V

3 V . O O O . V

2 . . . V V . .

1 # . V V . . #

a b c d e f g

Recommended Move: c1c2

Evaluation: 13 (2989600 nodes) (2.09s)

Make a move: c1c2

7 # . V V V . #

6 . . . V . . .

5 V . O O O . V

4 V V O K O V V

3 V . O O O . V

2 . . V V V . .

1 # . . V . . #

a b c d e f g

Recommended Move: c3b3

Evaluation: 14 (9128178 nodes) (7.52s)

Make a move:

By the way, playing through the engine line results in an attacker victory. Here’s the position where the engine first detects the win.

7 # . . V V . #

6 . . V V . V .

5 V V O . O V .

4 V . O # K V .

3 V . V V V . .

2 . . . . . . .

1 # . V . . . #

a b c d e f g

The sequence c5d5, f6e6; c4c5, c3c4; kd4, e3e4; d5c5, d6d5 polishes off the king