Ard Ri in Rust, Part 1

Published:

Question. Whether an Ard Ri engine can be written in Rust?

Objection. There is no rule set for Ard Ri that is universally agreed on. If the answer is yes, then such an engine must account for all possible variations in rules. That is annoying, and people cannot do annoying things, and therefore such an engine cannot be written in Rust, C, or Greek for that matter.

Reply to Objection. For practical purposes, a single rule set can be chosen and the engine instructed to play that variant of Ard Ri. By regrouping the expression “an (Ard Ri) engine” as “(an Ard Ri) engine,” one sees that any engine that can play a single variant of Ard Ri is, by definition, an Ard Ri engine.

Objection. Rust is not a good language for an Ard Ri engine. It is complicated and hard to use. It is especially hard to use for parallel processing, which is important for game engines. It also has a funny name.

Reply to Objection. Rust is a low level language. It is powerful like a large hamster and fast like a small hamster. I am bad at Rust and would like to get better.

I ANSWER that it is possible to write an Ard Ri engine in Rust. We will choose the following set of rules:

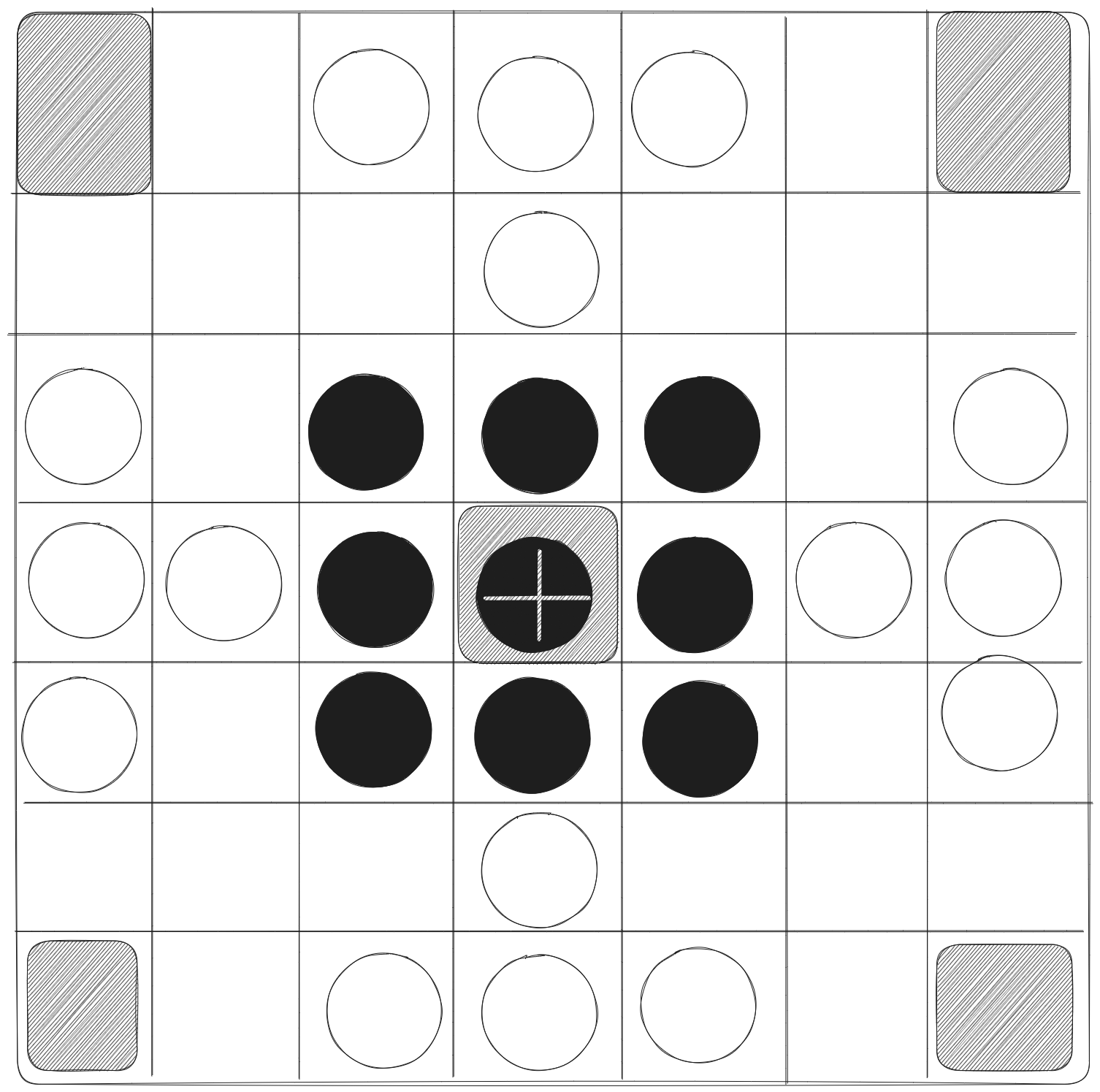

- The game is played on a 7x7 grid with 16 attackers, 8 defenders and one king configured as on the Wikipedia article

By convention, the defender will use the black pieces and the attacker the white pieces. We note that this is the exact opposite convention that everyone else uses; it’s only convenient because it preserves the chess convention. Since you probably haven’t heard of Ard Ri, I think it’ll be okay.

- Players alternate turns moving a single piece.

- The defender wins if their king makes it to one of the four corner squares.

- The attacker wins if the king is captured.

- All pieces move the same way: one square vertically or horizontally to an unoccupied square.

- The shaded gray squares (the four corners and the central square) are off limits to all pieces except the king.

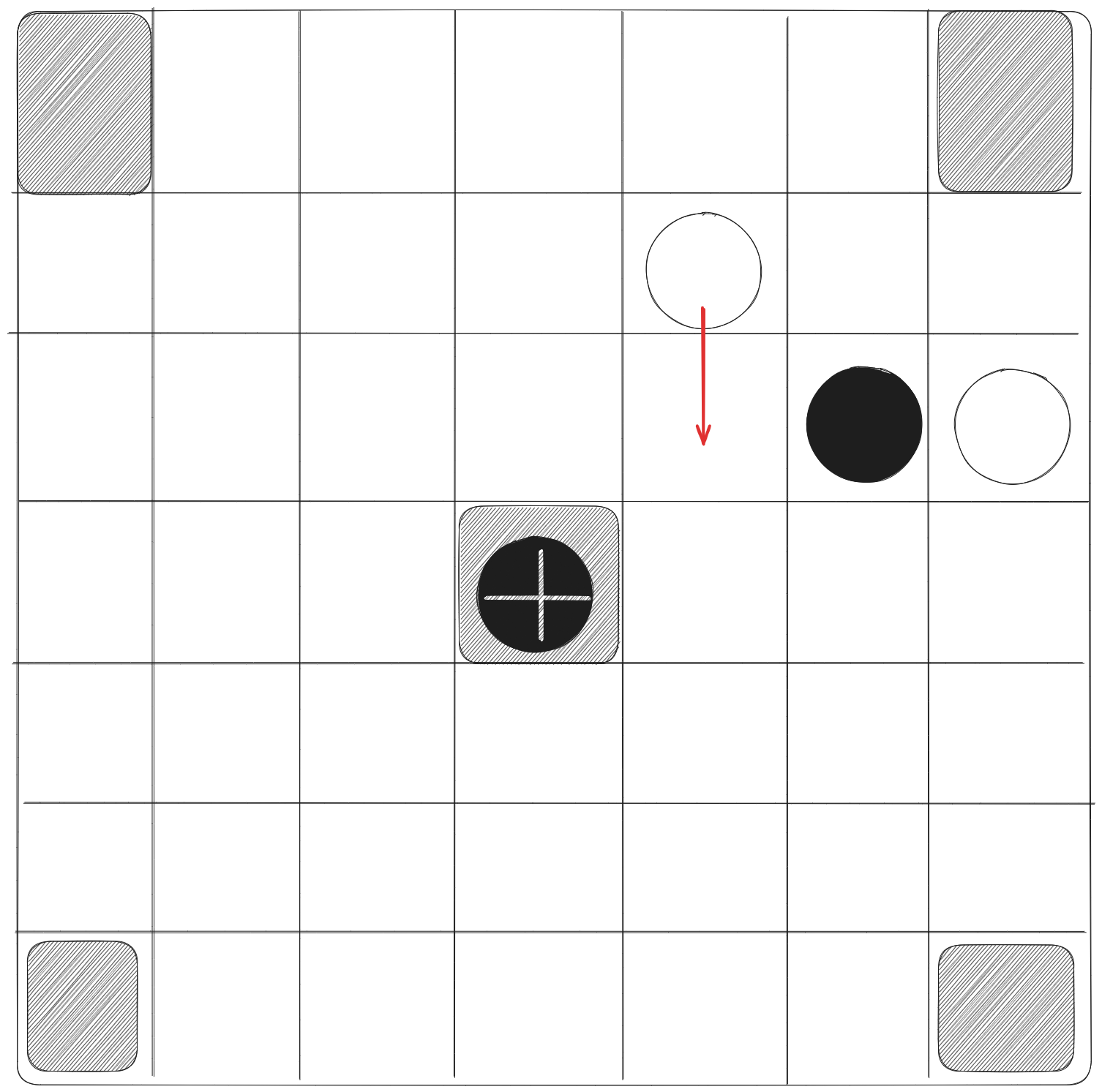

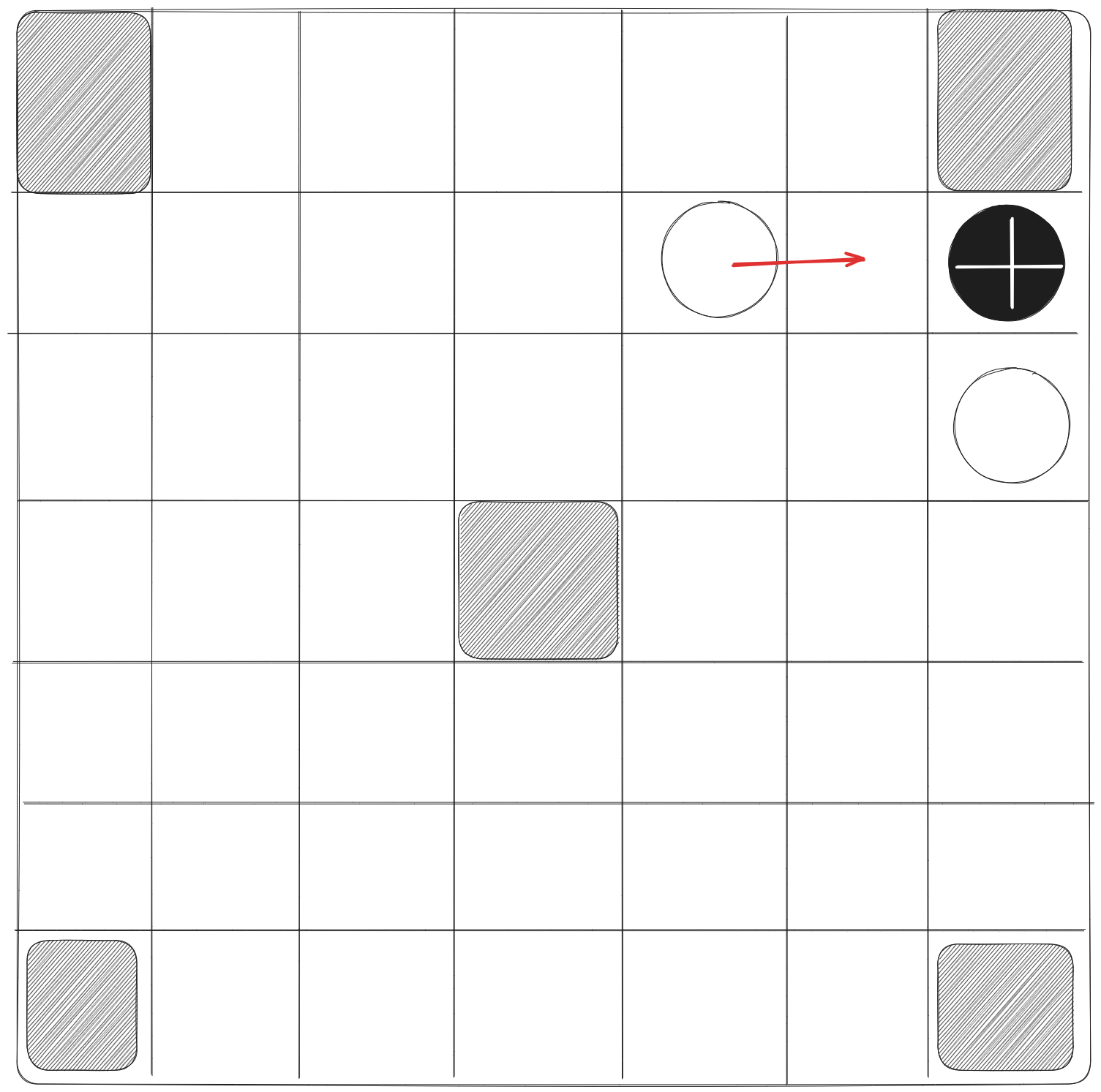

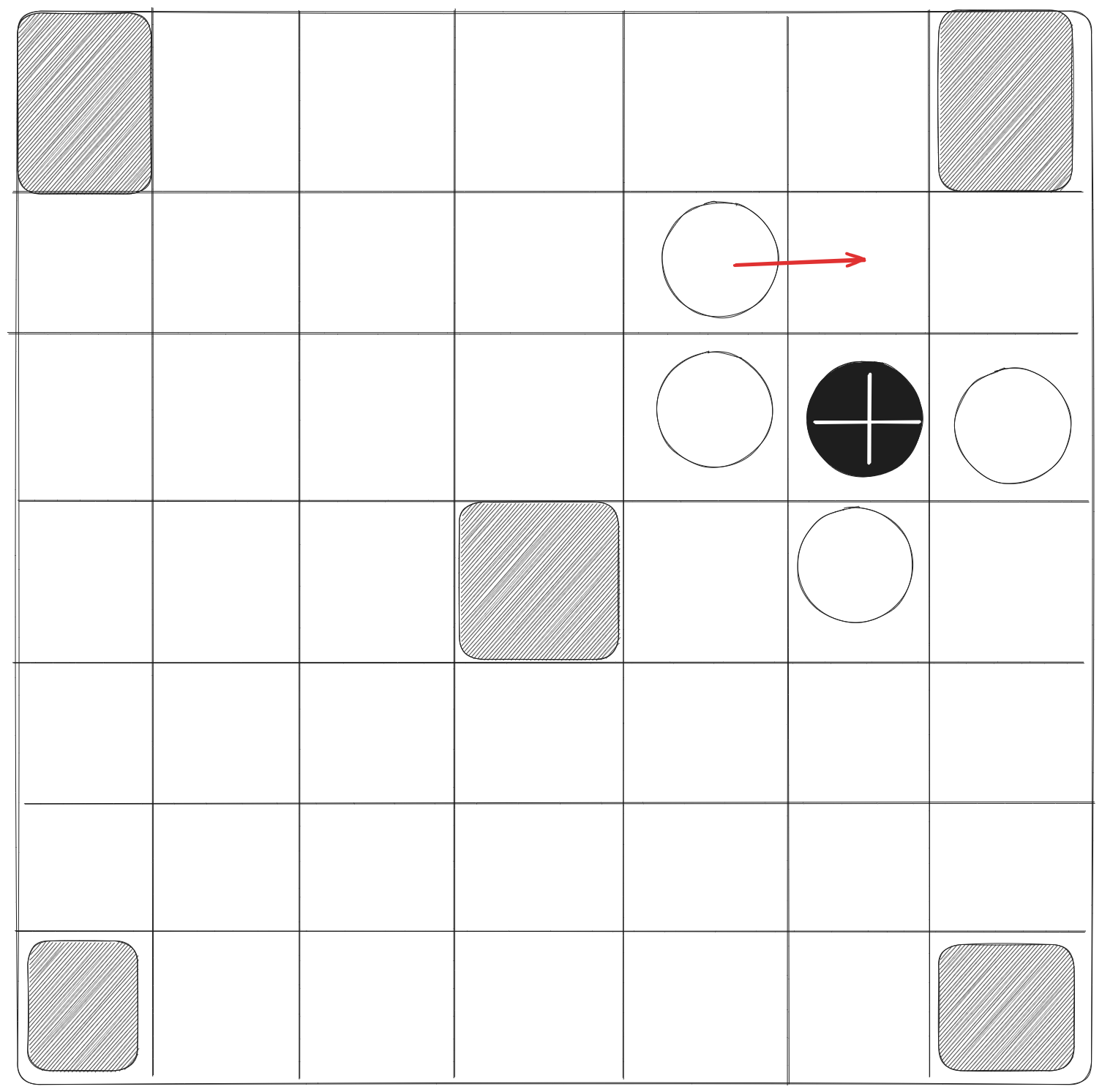

- A non-king piece is captured by double custodianship, i.e., if a piece has two enemy pieces on either side of it so that all three pieces form a vertical or horizontal segment. The middle piece is captured and removed from the board. The example below shows a black piece being captured.

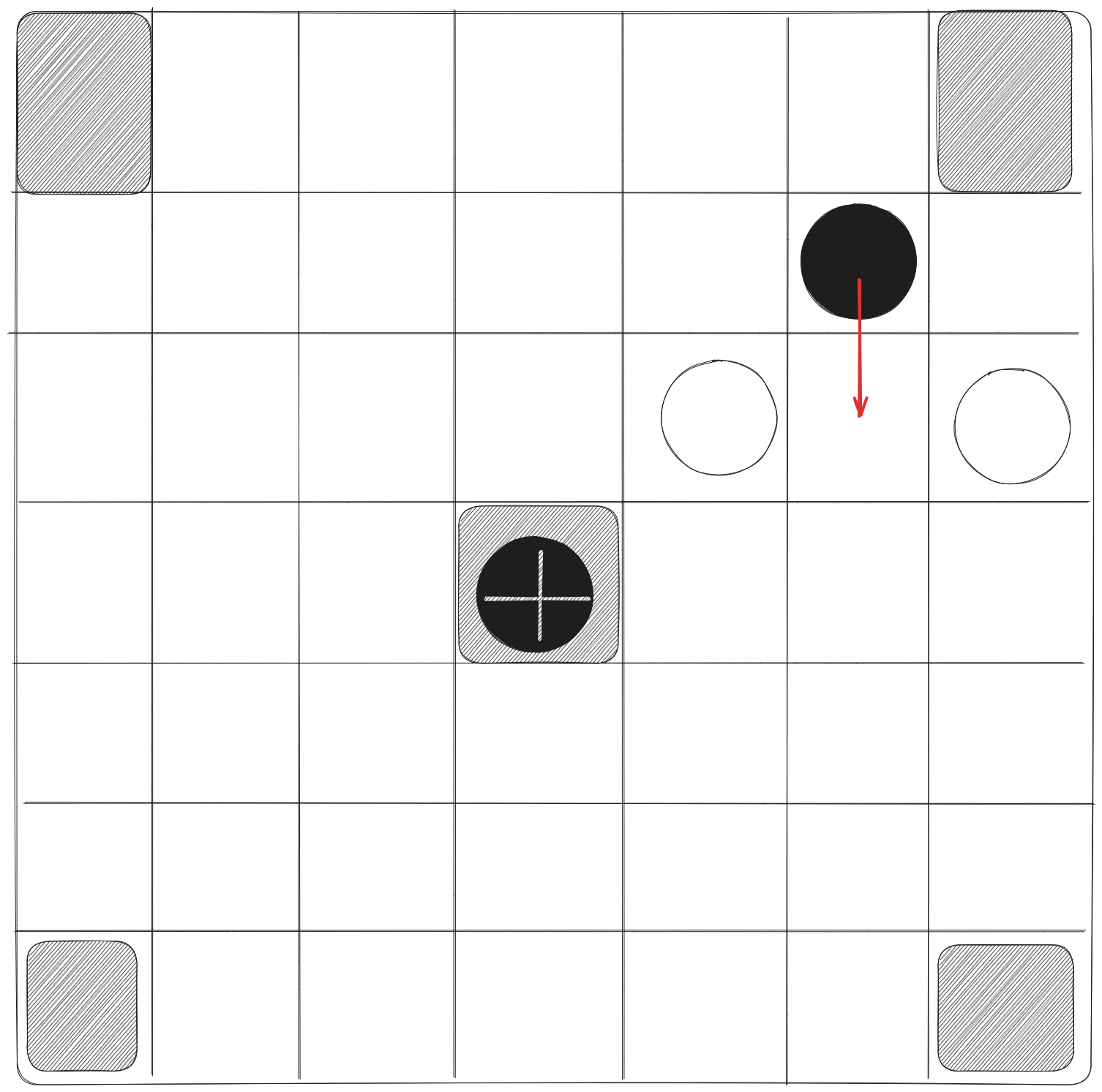

- A piece is only captured when the other player makes a move into capturing position. That is, if a white piece is moved between two black pieces or vice-versa, then that piece is not captured. In the example below, there is no capture.

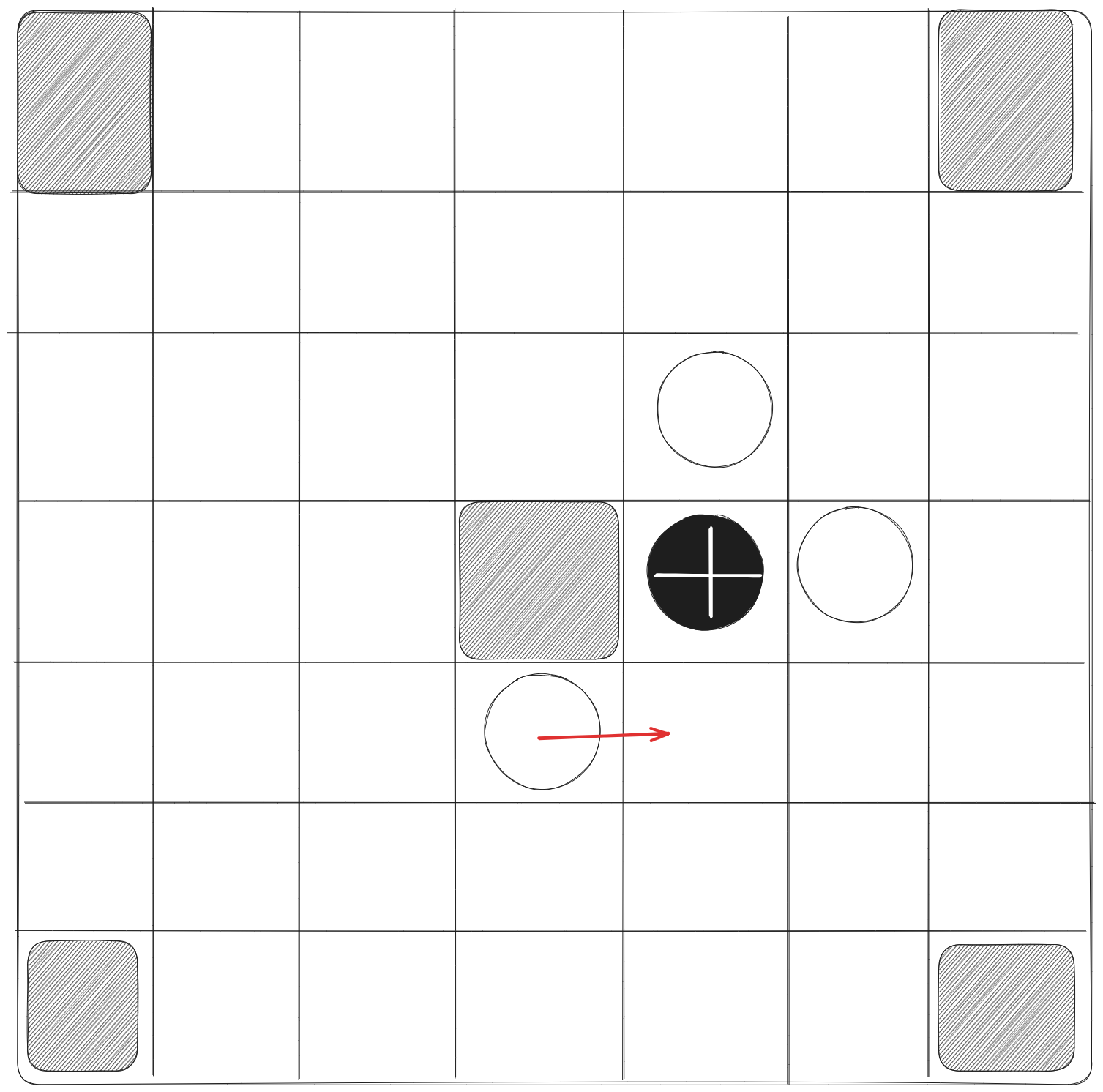

- The king is captured by full custodianship, which means that it must be surrounded by four attackers or three attackers and an off-limit square or two attackers, an off-limit square, and the edge of the board.

Representing the game in Rust

To represent the game in code, we start with a core concept from chess programming: bitboards. Naively, we might be inclined to define some kind of enum with an entry for each piece type; the game state would then be a 2d array with 49 (7x7) elements, each of which is the piece type at the corresponding square in the grid.

For reasons that will become clear, we can do a lot better than this both in terms of memory efficiency and computational efficiency. The standard way to represent the game state is with an array of bits for each piece type. For Ard Ri, we will have three bitboards: one for defender pieces, one for the king, and one for attacker pieces. Each bitboard will tell us, for each square on the game board, whether a piece of that type is there.

But we won’t even use something like [[bool; 7]7] to store a bitboard. There are 49 squares, which means that each bitboard requires only 49 bits. Therefore a bitboard will just be a u64.

// board.rs

pub type Bitboard = u64;

pub const BOARD_SIZE: u64 = 7;

The Board type will just be a bitboard for each piece type, plus one to keep track of the offlimit squares. We’ll also add three booleans to track (a) whose turn it is, (b) whether the attacker has won, and (c) whether the defender has won. These will help us, eventually, in evaluating positions very quickly.

// board.rs

pub struct Board {

pub attacker_board: Bitboard,

pub defender_board: Bitboard,

pub king_board: Bitboard,

pub offlimits_board: Bitboard,

pub attacker_move: bool,

pub attacker_win: bool,

pub defender_win: bool,

}

We’ll also add some convenience functions to help us convert between the index of a bit in a bitboard and the row and column on the board. We think of the least significant bit as representing coordinates (0, 0). The next bit is (0, 1), and so on, until the 49th bit. The remaining bits are not used.

// board.rs

pub fn rc_to_index(row: u64, col: u64) -> u64 {

row * BOARD_SIZE + col

}

pub fn index_to_rc(index: u64) -> (u64, u64) {

(index / BOARD_SIZE, index % BOARD_SIZE)

}

pub fn inbounds(row: isize, col: isize) -> bool {

return row >= 0 && row < BOARD_SIZE as isize && col >= 0 && col < BOARD_SIZE as isize;

}

Since the king is very special, we add a method to Board to find the king.

// board.rs

impl Board {

pub fn king_coordinates(&self) -> (u64, u64) {

for i in 0..BOARD_SIZE * BOARD_SIZE {

if self.king_board & (1 << i) != 0 {

return index_to_rc(i);

}

}

return (0, 0);

}

}

This is our first contact with the bitboards per se. We can identify whether a bitboard bb has a bit at index i using bb & (1 << i): if this is zero, then the ith bit of b is zero. Otherwise it has value 1.

For debugging and, ultimately, UI purposes, we add a function that converts a Board into a string.

// board.rs

impl Board {

// ...

pub fn to_string(&self) -> String {

let mut s = String::new();

for i in (0..BOARD_SIZE).rev() {

s.push((i + 1 + ('0' as u64)) as u8 as char);

s.push(' ');

for j in 0..BOARD_SIZE {

let index = rc_to_index(i as u64, j as u64);

if self.attacker_board & (1 << index) != 0 {

s.push('V');

} else if self.king_board & (1 << index) != 0 {

s.push('K');

} else if self.defender_board & (1 << index) != 0 {

s.push('O');

} else if self.offlimits_board & (1 << index) != 0 {

s.push('#');

} else {

s.push('.');

}

s.push(' ');

}

s.push('\n');

}

s.push_str(" ");

for j in 0..BOARD_SIZE {

s.push((j + ('a' as u64)) as u8 as char);

s.push(' ');

}

s.push('\n');

return s;

}

}

This function will make the starting position print out like this:

7 # . V V V . #

6 . . . V . . .

5 V . O O O . V

4 V V O K O V V

3 V . O O O . V

2 . . . V . . .

1 # . V V V . #

a b c d e f g

The king is represented by K, defenders by O, and attackers by V. The # symbol shows the offlimits squares, but only when they’re unoccupied.

Move generation

One of the most important parts of the engine is move generation. This is the process by which the valid moves are generated so that the engine can evaluate each of them. To start, we define a Move type

// board.rs

#[derive(Clone, Copy)]

pub struct Move {

pub start_row: u64,

pub start_col: u64,

pub end_row: u64,

pub end_col: u64,

pub king_move: bool,

}

Let’s not worry too much about optimization yet. The Move type simply tracks where a move starts and where it ends. It doesn’t worry about whether it’s an attacker move or a defender move (there can only be one piece at a given square), but it does track whether it was a king move or not. The reason to make a special exception for king moves is that king moves have an extra thing to check: whether the game is over. Tracking whether the move was a king move allows us to skip having to compute that for ourselves.

We also add a to_string() method to the Move type, plus the obvious implementation of PartialEq.

// board.rs

impl Move {

pub fn to_string(&self) -> String {

let mut s: String;

if self.king_move {

s = "k".to_string();

} else {

s = ((self.start_col as u8 + 'a' as u8) as char).to_string();

s.push_str(&(self.start_row + 1).to_string());

}

s.push((self.end_col as u8 + 'a' as u8) as char);

s.push_str(&(self.end_row + 1).to_string());

return s;

}

}

impl PartialEq for Move {

fn eq(&self, other: &Self) -> bool {

if self.king_move && other.king_move {

return self.end_row == other.end_row && self.end_col == other.end_col;

}

return self.start_row == other.start_row

&& self.start_col == other.start_col

&& self.end_row == other.end_row

&& self.end_col == other.end_col

&& self.king_move == other.king_move;

}

fn ne(&self, other: &Self) -> bool {

if self.king_move && other.king_move {

return self.end_row != other.end_row || self.end_col != other.end_col;

}

return self.start_row != other.start_row

|| self.start_col != other.start_col

|| self.end_row != other.end_row

|| self.end_col != other.end_col

|| self.king_move != other.king_move;

}

}

Making moves

Now we want to add a method to Board that makes a move. It should have signature

impl Board {

fn make_move(&self, m: Move) -> Board {}

}

To simplify the logic, we’ll handle attacker moves, king moves, and non-king defender moves separately. Starting with attacker moves, first convert the Move coordinates into u64 indices, then update

impl Board {

pub fn make_attacker_move(&self, m: Move) -> Board {

let mut new_board = Board {

attacker_board: self.attacker_board,

defender_board: self.defender_board,

king_board: self.king_board,

offlimits_board: self.offlimits_board,

attacker_move: false,

attacker_win: false,

defender_win: false,

stalemate: false,

};

let index = rc_to_index(m.start_row, m.start_col);

let new_index = rc_to_index(m.end_row, m.end_col);

new_board.attacker_board &= !(1 << index); // remove the 1 at index

new_board.attacker_board |= 1 << new_index; // add a 1 at new_index

//...

}

}

Before we return the new_board, we need to check a few things.

- Was the king captured?

- Was a capture made?

We’re going to add a separate method to check if the king was captured, so we punt on that for now. To check captures, we need to check if the attacker we just moved is now in a position of double custodianship of a defender. Since the directions we need to check are always the same, we add them as a constant:

// board.rs

pub const DIRS: [(isize, isize); 4] = [(0, 1), (0, -1), (1, 0), (-1, 0)];

Now we can iterate over DIRS and check if the piece we moved is capturing a defender in any of the four directions. We’re going to punt on that too and assume the existence of a valid_capture function that determines whether a piece on one bitboard is capturing a piece on another bitboard.

pub fn make_attacker_move(&self, m: Move) -> Board {

// ...

let (king_row, king_col) = self.king_coordinates();

let mut next_to_king = false;

for dir in DIRS.iter() {

let new_row = m.end_row as isize + dir.0;

let new_col = m.end_col as isize + dir.1;

if inbounds(new_row, new_col) && new_row == king_row as isize && new_col == king_col as isize {

next_to_king = true;

break;

}

}

if new_board.king_captured() && next_to_king { // not yet implemented

new_board.attacker_win = true;

}

for dir in DIRS.iter() {

let new_row = m.end_row as isize + dir.0;

let new_col = m.end_col as isize + dir.1;

if valid_capture( //as yet not implemented

&self.attacker_board,

&self.defender_board,

(m.end_row as isize, m.end_col as isize),

(new_row, new_col),

) {

let defender_index = rc_to_index(new_row as u64, new_col as u64);

new_board.defender_board &= !(1 << defender_index); // remove the captured piece from the board

}

}

return new_board;

}

Now I owe you two things: king_captured and valid_capture. Let’s do valid_capture first. The logic is pretty simple. It takes a capturer bitboard, a capturee bitboard (we do it like this to avoid duplicating the logic for defenders capturing attackers), plus the coordinates of the piece that moved (capturer_coords) and the coordinates where a piece might be captured (capturee_coords). The function returns true if

- there is a piece on

capturee_bitboardatcapturee_coordsand - there is a piece on

capturer_bitboardin double custodianship withcapturer_coords

// board.rs

fn valid_capture(

capturer_bitboard: &Bitboard,

capturee_bitboard: &Bitboard,

capturer_coords: (isize, isize),

capturee_coords: (isize, isize),

) -> bool {

// no out-of-bounds captures

if !inbounds(capturee_coords.0, capturee_coords.1) {

return false;

}

if !inbounds(capturer_coords.0, capturer_coords.1) {

return false;

}

let capturee_index = rc_to_index(capturee_coords.0 as u64, capturee_coords.1 as u64);

// check if there's a piece at capturee_index

if capturee_bitboard & (1 << capturee_index) == 0 {

return false;

}

// look for double custodianship

let ally_coords = (

2 * (capturee_coords.0 - capturer_coords.0) + capturer_coords.0,

2 * (capturee_coords.1 - capturer_coords.1) + capturer_coords.1,

);

if !inbounds(ally_coords.0, ally_coords.1) {

return false;

}

let ally_index = rc_to_index(ally_coords.0 as u64, ally_coords.1 as u64);

return capturer_bitboard & (1 << ally_index) != 0;

}

To complete make_attacker_move, we need the king_captured method. The logic is similar, but since there’s only one king. We start by taking its coordinates, then checking all four directions.

// board.rs

impl Board {

// ...

pub fn king_captured(&self) -> bool {

let (king_row, king_col) = self.king_coordinates();

for dir in DIRS.iter() {

let new_row = king_row as isize + dir.0;

let new_col = king_col as isize + dir.1;

if !inbounds(new_row, new_col) {

continue;

}

let new_index = rc_to_index(new_row as u64, new_col as u64);

if self.offlimits_board & (1 << new_index) != 0 {

continue;

}

if !self.attacker_board & (1 << new_index) != 0 {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

}

We write a make_defender_move function that is basically the same as make_attacker_move, with one small addition: since the king can help capture (the king is armed), when we call valid_capture, we use the bitwise OR of the defender and king bitboards as the capturer_bitboard argument. This is one of the benefits of storing bitboards as integers. A bitwise OR operation requires a single processor cycle. This won’t help us much for now, but when we make transposition tables, this will dramatically speed up calculation times.

We finish off all move types with make_king_move. This is similar to make_defender_move except we also check if the king made it to a corner square, in which case the game is over. The king can capture, so we check for captures.

// board.rs

impl Board {

// ...

fn make_king_move(&self, m: Move) -> Board {

let mut new_board = Board {

attacker_board: self.attacker_board,

defender_board: self.defender_board,

king_board: self.king_board,

offlimits_board: self.offlimits_board,

attacker_move: true,

attacker_win: false,

defender_win: false,

stalemate: false,

};

let (king_row, king_col) = self.king_coordinates();

let index = rc_to_index(king_row, king_col);

let new_index = rc_to_index(m.end_row, m.end_col);

new_board.king_board &= !(1 << index);

new_board.king_board |= 1 << new_index;

// check if the king reached a corner

if (m.end_col == 0 && m.end_row == 0)

|| (m.end_col == BOARD_SIZE - 1 && m.end_row == 0)

|| (m.end_col == BOARD_SIZE - 1 && m.end_row == BOARD_SIZE - 1)

|| (m.end_col == 0 && m.end_row == BOARD_SIZE - 1)

{

new_board.defender_win = true;

}

let capturer_bitboard = &self.defender_board | &self.king_board;

for dir in DIRS.iter() {

let new_row = m.end_row as isize + dir.0;

let new_col = m.end_col as isize + dir.1;

if valid_capture(

&capturer_bitboard,

&self.attacker_board,

(m.end_row as isize, m.end_col as isize),

(new_row, new_col),

) {

let attacker_index = rc_to_index(new_row as u64, new_col as u64);

new_board.attacker_board &= !(1 << attacker_index);

}

}

return new_board;

}

}

We wrap all the move types up into a single method.

// board.rs

impl Board {

pub fn make_move(&self, m: Move) -> Board {

if m.king_move {

return self.make_king_move(m);

} else if self.attacker_move {

return self.make_attacker_move(m);

}

return self.make_defender_move(m);;

}

}

A final convenience method allows us to convert boolean arrays into bitboards.

// board.rs

pub fn bool_array_to_bitboard(arr: [[bool; BOARD_SIZE as usize]; BOARD_SIZE as usize]) -> Bitboard {

let mut b: Bitboard = 0;

for i in 0..BOARD_SIZE {

for j in 0..BOARD_SIZE {

if arr[i as usize][j as usize] {

b |= 1 << rc_to_index(i, j);

}

}

}

return b;

}

Generating moves

Situation report: our board can make moves, but we have no way of verifying whether moves are legal! To solve this, we’ll algorithmically generate all valid moves from a board state. We’re going to do this as an Iterator, rather than a Vec or something in order to save memory. This sounds stupid now, but when our Ard Ri engine is processing tens of thousands of nodes per second, we will be very happy to have a lazy evaluation strategy. To get started, we define our MoveGenerator type.

Here’s how it works: iterate over the 49 squares of the board. If there’s a piece at the current square, add its valid moves to a “cache.” Prioritize emptying the cache over traversing to the next square.

// movegen.rs

use crate::board::{inbounds, index_to_rc, rc_to_index, Bitboard, Board, Move, BOARD_SIZE, DIRS};

pub struct MoveGenerator<'a> {

pub board: &'a Board,

pub index: u64,

pub cached: Vec<Move>,

}

impl<'a> MoveGenerator<'a> {

pub fn new(board: &'a Board) -> Self {

MoveGenerator {

board,

index: 0,

cached: Vec::new(),

}

}

}

Before we implement the trait, let’s think about how valid moves can be determined. We need to check all four DIRS directions and determine if they are both in-bounds and unoccupied. If so, the piece may move there. This logic is independent of piece type, but “out-of-bounds” means something different for kings. So we define a function that takes a piece position and an occupied bitboard and returns a vector of valid final positions. We’ll call this output a vector of “pieceless moves,” i.e., moves that have forgotten what kind of piece was moved.

// movegen.rs

struct PiecelessMove {

from: (u64, u64),

to: (u64, u64),

}

fn gen_moves_one_piece(index: u64, occupied: Bitboard) -> Vec<PiecelessMove> {

let mut moves = Vec::new();

let (row, col) = index_to_rc(index);

for &(dr, dc) in DIRS.iter() {

let new_row = row as isize + dr;

let new_col = col as isize + dc;

if !inbounds(new_row, new_col) {

continue;

}

let new_index = rc_to_index(new_row as u64, new_col as u64);

if occupied & (1 << new_index) == 0 {

moves.push(PiecelessMove {

from: (row, col),

to: (new_row as u64, new_col as u64),

});

}

}

return moves;

}

To generate attacker moves, we just feed this function an attacker and the bitwise OR of all the bitboards.

// movegen.rs

fn gen_attacker_moves(board: &Board, index: u64) -> Vec<Move> {

let mut moves = Vec::new();

if board.attacker_board & (1 << index) != 0 {

let occupied =

board.attacker_board | board.defender_board | board.king_board | board.offlimits_board;

let piece_moves = gen_moves_one_piece(index, occupied);

for m in piece_moves {

moves.push(Move {

start_row: m.from.0,

start_col: m.from.1,

end_row: m.to.0,

end_col: m.to.1,

king_move: false,

});

}

}

return moves;

}

Defender moves and king moves are handled similarly:

// movegen.rs

fn gen_defender_moves(board: &Board, index: u64) -> Vec<Move> {

let mut moves = Vec::new();

// non-king moves

if board.defender_board & (1 << index) != 0 {

let occupied =

board.attacker_board | board.defender_board | board.king_board | board.offlimits_board;

let piece_moves = gen_moves_one_piece(index, occupied);

for m in piece_moves {

moves.push(Move {

start_row: m.from.0,

start_col: m.from.1,

end_row: m.to.0,

end_col: m.to.1,

king_move: false,

});

}

return moves;

}

// king moves

if board.king_board & (1 << index) != 0 {

let occupied = board.attacker_board | board.defender_board | board.king_board;

let piece_moves = gen_moves_one_piece(index, occupied);

for m in piece_moves {

moves.push(Move {

start_row: m.from.0,

start_col: m.from.1,

end_row: m.to.0,

end_col: m.to.1,

king_move: true,

});

}

}

return moves;

}

Finally, we can generate all valid moves in the position by implementing Iterator for MoveGenerator.

// movegen.rs

impl<'a> Iterator for MoveGenerator<'a> {

type Item = Move;

fn next(&mut self) -> Option<Self::Item> {

// prioritize cached moves

if self.cached.len() > 0 {

return Some(self.cached.pop().unwrap());

}

let mut from_pos = Vec::new();

while from_pos.is_empty() {

// end iteration if we reach the final index

if self.index >= BOARD_SIZE * BOARD_SIZE {

return None;

}

if self.board.attacker_move {

from_pos = gen_attacker_moves(&self.board, self.index);

} else {

from_pos = gen_defender_moves(&self.board, self.index);

}

// move to the next index

self.index += 1

}

self.cached = from_pos;

return Some(self.cached.pop().unwrap());

}

}

Can we play now?

We need a UI! Here’s a trait for a minimally functional Ard Ri UI.

// ui.rs

pub trait UI {

fn get_move(&mut self) -> Move;

fn render_board(&self, b: &Board);

fn invalid_move(&self);

fn attacker_win(&self);

fn defender_win(&self);

}

I implemented this with a very dodgy command line UI. You can do it however you want. Now we can play Ard Ri! (Note: the starting bitboards were computed with bool_array_to_bitboard.)

// main.rs

use std::time::Instant;

use movegen::MoveGenerator;

use ui::UI;

mod board;

mod movegen;

mod ui;

fn init_board() -> board::Board {

return board::Board {

attacker_board: 123437837206556, // trust me on this lol

defender_board: 7558594560,

king_board: 16777216,

offlimits_board: 285873039999041,

attacker_move: false,

attacker_win: false,

defender_win: false,

stalemate: false,

};

}

fn main() {

let mut b = init_board();

let mut console_ui = ui::ConsoleUI::new();

loop {

if b.defender_win {

console_ui.defender_win();

break;

} else if b.attacker_win {

console_ui.attacker_win();

break;

}

console_ui.render_board(&b);

let mut mv = console_ui.get_move();

let legal_moves = MoveGenerator::new(&b).collect::<Vec<_>>();

while !legal_moves.contains(&mv) {

console_ui.invalid_move();

mv = console_ui.get_move();

}

b = b.make_move(mv);

}

}

In my text UI, it looks like this:

7 # . V V V . #

6 . . . V . . .

5 V . O O O . V

4 V V O K O V V

3 V . O O O . V

2 . . . V . . .

1 # . V V V . #

a b c d e f g

Make a move:

If I enter c3c2, I get this:

7 # . V V V . #

6 . . . V . . .

5 V . O O O . V

4 V V O K O V V

3 V . . O O . V

2 . . O V . . .

1 # . V V V . #

a b c d e f g

Make a move:

Wrap up

We can play Ard Ri, but we want an engine to tell us how to do it. Our next goal is to build a minimally functional Ard Ri engine. It won’t be very good, but it will work. From there, we will make many incremental improvements until we get an engine that is better than us at the game. (Okay, this is a low bar.)

A rough outline of our trajectory looks like this:

- minimax engine

- alpha-beta pruning

- transposition tables

- iterative deepening

- principal variations

- NNUE evaluation